One question many have asked is whether or not cryptocurrency markets have enough liquidity to allow for mass sanctions evasion or capital flight by Russian oligarchs. In finance, liquidity refers to how much money is available for a particular asset to be sold quickly, without affecting its price. The price component of liquidity is especially important here. According to Chainalysis if one were to try and sell a large quantity of an illiquid asset, it would likely bring down the asset’s price, decreasing the value available to the seller. We’ve seen examples of this in crypto markets previously, such as in 2019 when the scammers behind the PlusToken Ponzi scheme unloaded so much Bitcoin onto the market that many believed it lowered Bitcoin’s price. If markets are in fact not liquid enough to support extremely large sell-offs of different types of crypto assets, then cryptocurrency would be a less attractive means of sanctions evasion for designated Russian elites, though this wouldn’t preclude relevant actors from converting cash into cryptocurrency in order to hide it.

In this blog, we try to answer this question by measuring the liquidity of cryptocurrency markets. Our findings suggest that the markets aren’t liquid enough to support the movement of the hundreds of billions controlled by sanctioned Russian oligarchs. This reinforces our belief that any Russian sanctions evasion using cryptocurrency will most likely resemble typical money laundering, in which small amounts of cryptocurrency are moved to cashout services over time, rather than systematic, mass conversions between cryptocurrency and cash.

Connecting liquidity to Russian sanctions evasion

The first question we have to answer: How much wealth do sanctioned Russian actors actually hold? This is difficult to know, as much of this wealth is stored in equities and other financial instruments, while cash is dispersed across bank accounts around the world, not to mention illiquid, physical assets like real estate and yachts. There’s no publicly available audit of all those disparate assets. Vladimir Putin himself provides a great example of why measuring oligarch wealth is so hard. While his Kremlin-listed salary is $140,000, Putin is rumored to have $200 billion in assets hidden away, which would make him the richest person in the world.

The Bloomberg Billionaires Index lists 22 Russian nationals with a combined wealth of just over $300 billion, but of course not all of these individuals have been sanctioned, and not all sanctioned Russian oligarchs are billionaires — many are “only” centimillionaires. Meanwhile, a 2017 study from the National Economic Bureau estimated that Russian oligarchs hold roughly $800 billion in offshore funds. While this number doesn’t account for assets held within Russia, we’ll use it in this analysis, as it’s one of the largest reliable estimates available, which decreases our risk of under-counting.

Next, we’ll look at three different metrics we can use to calculate liquidity in cryptocurrency markets, and compare them to that $800 billion figure.

Free float

One metric we use to measure liquidity in cryptocurrency markets is free float.Free float measures the total value of a given crypto asset held by liquid entities, which we define as entities that both:

- Send at least 25% of assets they receive in a given year

- Have held all of their assets for a year or less on average

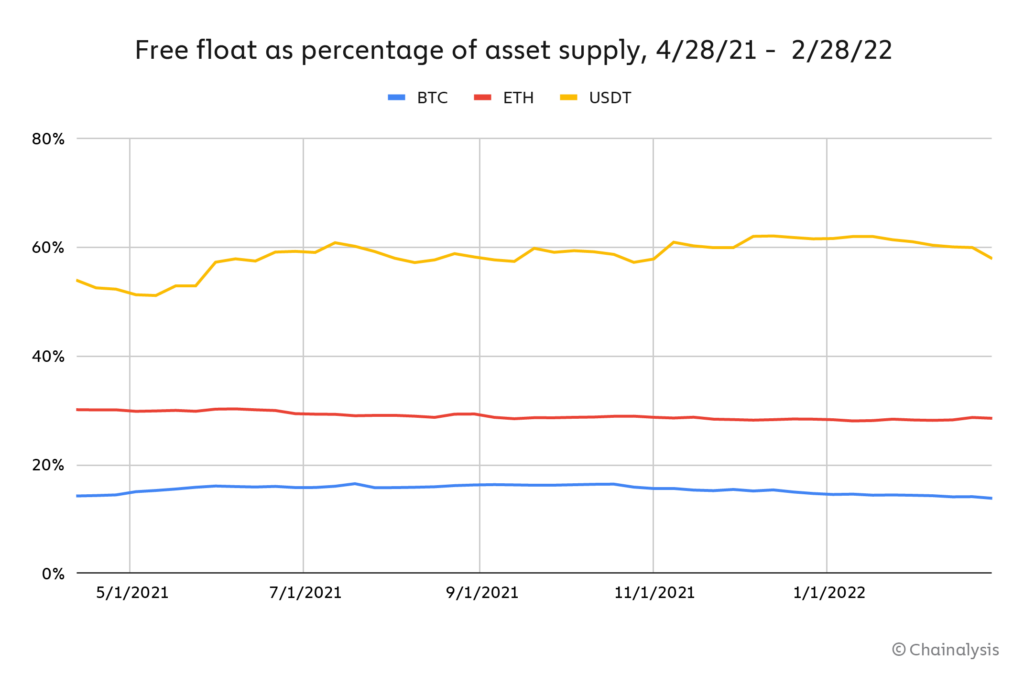

In short, free float is designed to measure the value of an asset held by entities that are likely to circulate that asset based on their previous behavior. Please note that entities here can mean both private wallets and services like exchanges — all that matters is that they meet our criteria above. Below, we compare the three cryptocurrencies with the biggest market capitalizations by total supply and percent of all value in free float.

| Asset | Percent of supply in free float | Supply in free float |

| BTC | 14% | $127 B |

| ETH | 29% | $49 B |

| Tether | 60% | $120 B |

We see that while Bitcoin has the lowest share of overall supply in free flat at just 14%, its overall market capitalization is high enough that this 14% gives Bitcoin the largest overall free floating supply when priced in U.S. dollars. These numbers hold relatively constant over time, though Tether’s free float supply fluctuates a bit more than that of Bitcoin and Ethereum.

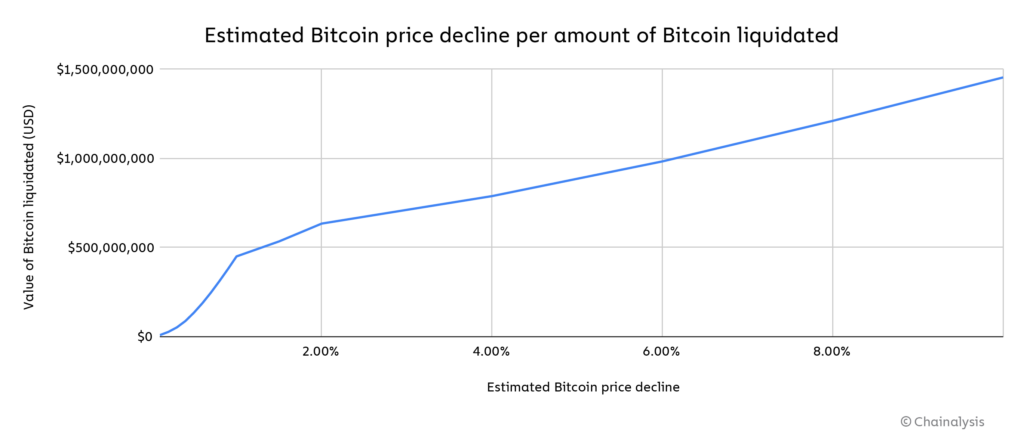

Overall, these three assets offer a combined $296 billion in free floating supply that we can expect the holder, based on past behavior, to move within a given year-long period — less than half of the estimated $800 billion held by Russian oligarchs. Furthermore, under these conditions, we would expect any attempt to liquidate billions of dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency to apply significant downward price pressure. Our models, based on an analysis of liquidations — that is, exchanges of Bitcoin for fiat currency — and subsequent price movements across 19 exchanges, estimate that Bitcoin’s price would decrease by 10% after the sale of just $1.46 billion worth of Bitcoin.

We would see similar dynamics in other cryptocurrencies like Ethereum as well, though with bigger price swings for smaller amounts sold given the lower supply in free float. In short, any attempt to liquidate $800 billion or even $100 billion worth of cryptocurrency would likely cause major price crashes, making large-scale Russian sanctions evasion with cryptocurrency infeasible.

Inflows to services

Analysis based on the free float metric establishes that cryptocurrency markets almost certainly couldn’t support mass liquidations of Russian oligarchs’ wealth from a price standpoint. But let’s take a step back and consider a different question: Could oligarchs even move that much wealth to a service where it could be liquidated to begin with?

Most cryptocurrency transaction volume takes place within or between services like exchanges. And crucially, centralized cryptocurrency services are the only places users can convert their cryptocurrency into cash so that it can be spent freely. Even ignoring the fact that the biggest cryptocurrency services are regulated and put users through KYC procedures upon signup — processes we would expect to catch a sanctioned actor — could Russian oligarchs move their wealth to cryptocurrency services without drawing the attention of law enforcement and compliance teams? Remember, like all transactions on the blockchain, transfers to services are publicly visible, and extremely large movements are a topic of conversation in the cryptocurrency community.

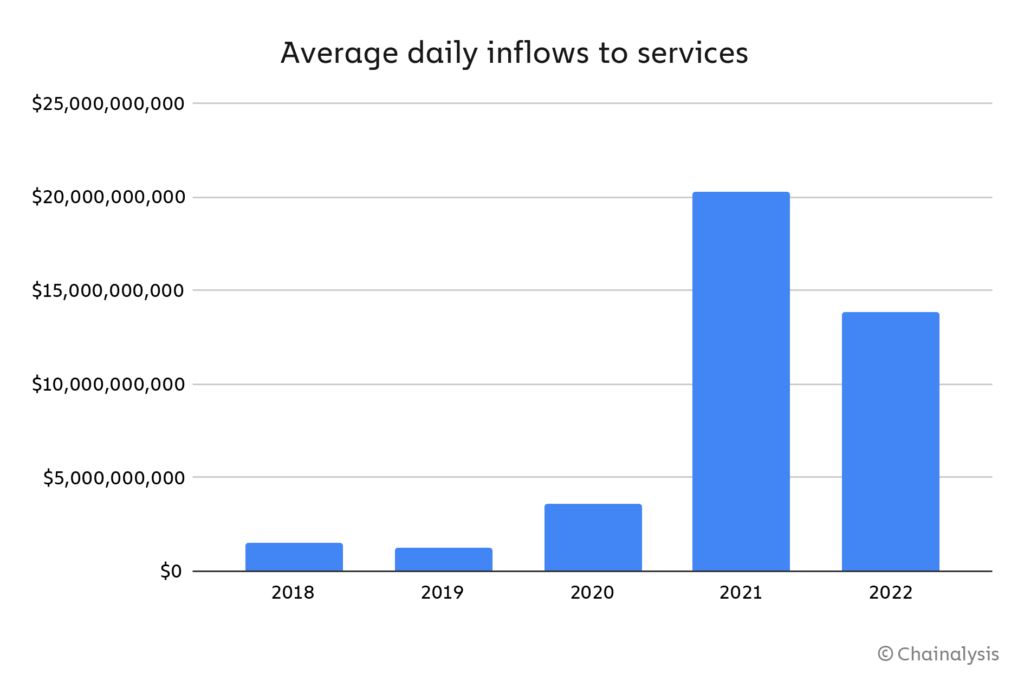

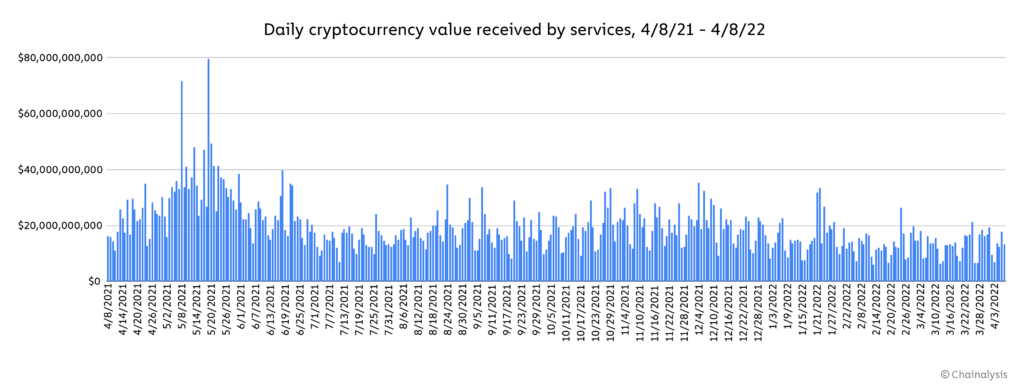

Let’s look at the data on cryptocurrency inflows to services.

On average in 2022, we’re seeing roughly $14 billion worth of cryptocurrency flow into cryptocurrency services every day, down from $20 billion in 2021.

However, inflows to services fluctuate significantly on a daily basis.

In the last year, daily inflows to services reached a high of $80 billion on May 19, 2021. It would take ten days of service inflows at that level for Russian oligarchs to move cryptocurrency equivalent to their wealth to a service where it could be liquidated. That would raise red flags not just for those services’ compliance teams, but for law enforcement and the cryptocurrency community at large.

Mixer liquidity

The metrics above look at private wallets and cryptocurrency services, which together represent a huge share of the overall cryptocurrency ecosystem. But what if we focus just on the liquidity for the types of services criminals typically use to move cryptocurrency?

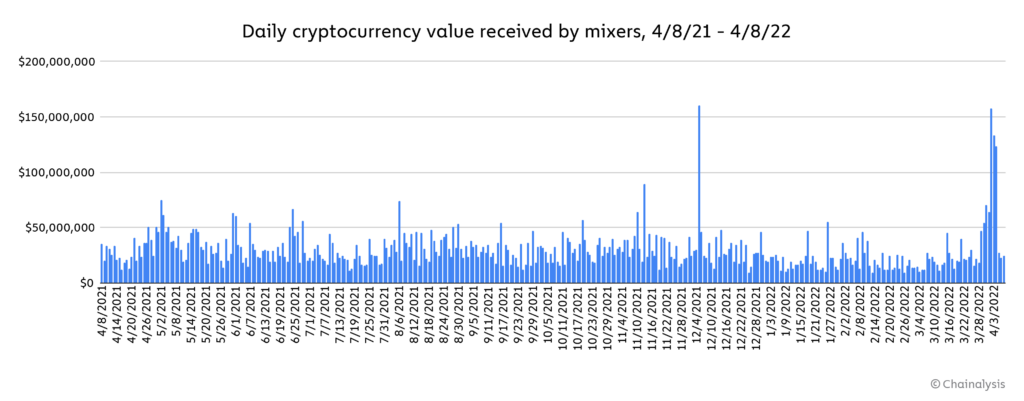

Mixers are a great example of such a service. While some mixers are compliant, and there are certainly non-criminal reasons to use them, we’ve shown previously that mixers are disproportionately favored by cybercriminals looking to launder money. We should also note that the liquidity question for mixers is different than for other services or for cryptocurrency markets as a whole, as it’s less about how much of an asset you can move without affecting price, but more about whether the mixer will actually be able to obfuscate your funds. Mixers work by taking cryptocurrency from multiple users, pooling it, and redistributing it back to users in a random mix, with each getting an equivalent to what they put in. This “breaks the chain,” so to speak, ensuring each user ends up with cryptocurrency that came from the other users and theoretically therefore can’t be traced back to its origin. However, if one user floods the mixer and contributes significantly more than the other users involved in the transaction, much of what they end up with will be made up of the funds they originally put in, making it easy to trace the funds back to their original source.

So, how much liquidity exists for mixers?

Over the last year, all mixers on average have received just under $30 million worth of cryptocurrency per day. However, as we see above, that number fluctuates significantly, reaching a high of $160 million on December 5, 2021. Even if Russian oligarchs sent $160 million worth of cryptocurrency per day to mixers — amounts that would likely render the mixers ineffective — it would take 5,000 days to move their $800 billion of wealth.

It’s worth noting that Chainalysis provides de-mixing capabilities, which may further disincentivize mixer usage.

Cryptocurrency-based sanctions evasion will likely be small in scale

By nearly any measure, cryptocurrency markets don’t have the liquidity to support Russian sanctions evasion en masse. The assets of sanctioned actors far exceed what one could hope to sell without either crashing the prices of crypto assets or drawing the attention of blockchain observers.

But that doesn’t mean sanctions evasion with cryptocurrency isn’t happening or could never happen. It just means that crypto-based sanctions evasion will look like other forms of money laundering we observe on the blockchains — small amounts of cryptocurrency gradually moved to cashout points. While that may mean the threat is reduced, it makes uncovering it even harder — these transactions would likely look like everyday transaction activity at first glance. It would take advanced solutions like Chainalysis, combined with standard financial investigation techniques, to trace the origins of the funds and connect them back to sanctioned individuals or entities.