The Bank of England and His Majesty’s Treasury announced a joint consultationinto the feasibility of issuing a digital pound this week. The move followed in the footsteps of the European Central Bank moving ahead with a similar plan earlier this year.

So is this all a question of central bank FOMO? Or is there any susbtance to the idea? We’ve read through the consultation working paper so you don’t have to (albeit not the technical one yet) and had a go at answering the consultation questions with a critical mindset.

Here are our responses (which flag most of our concerns):

The consultation paper foresees the need for a digital pound to offset the waning use of central bank-issued physical cash in the UK in the hope that such a security will provide an alternative anchor to help underpin the UK’s monetary and financial stability, as well as its sovereignty. It argues that convertibility of bank deposits into cash is an essential mechanism in supporting confidence in private money and the banking sector.

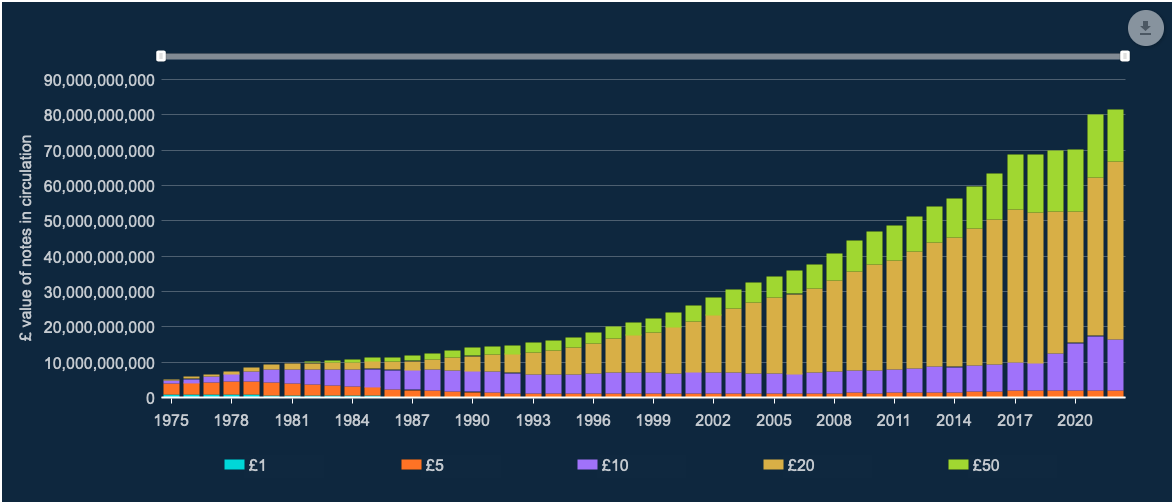

This presumption, however, overlooks that while digital transactions are increasingly popular and crowding out cash transactions in retail commerce, overall demand for physical banknotes continues to increase in the UK economy. According to Bank of England data, the value of banknotes in circulation in the UK economy rose to over £80bn in 2022 versus £70bn in 2020. It is not fair to assume, therefore, that “as cash continues to become less central and less usable in many people’s lives, central bank money will become less used for everyday transactions” or that “the decline in the use of cash is expected to continue as commerce and payments become more digital, even though UK authorities are committed to keeping cash available as long as there is demand for it.”

Whether cash use in retail transactions is declining or not has little bearing on its role as an anchor between private money and state money, especially in the context of growing circulation. The anchor also has the capacity to be preserved through the conventional bank reserve channel.

Asking whether the design of a digital pound meets objectives based on arbitrarily and subjective communicated primary motivations fails to address whether the motivations themselves are logical or well thought out. An active discussion about the motivations is required before going ahead with any design to address them.

While the consultation paper stresses that no decision about digital pound has been predetermined, the fact that the paper lacks a clear problem statement implies the opposite. The consultation appears to be a mere formality, rather than a bona fide inquiry into whether a digital pound is a good idea for the UK.

According to the consultation paper the BoE and HMT’s primary motivations for the digital pound are the availability of central bank money as an anchor for confidence and safety in money, and promoting innovation, choice, and efficiency in payments.

As already stated already, however, rising cash in circulation undermines the idea that a digital pound is needed to preserve a monetary anchor for confidence and safety in money because the physical one is waning. Even if cash in circulation were to decline, this needn’t undermine its role as a monetary anchor. The consultation notes that for a digital substitute “to achieve its objective as a monetary anchor, the digital pound would need to be widely available and usable, but does not need to be the dominant form of money for retail payments.” If that’s true of digital cash, this should also be true of physical cash. Arguing that the UK needs a digital pound to maintain a monetary anchor between its own liabilities and those of private issuers therefore does not square. No such need exists. This is especially the case if legal steps are taken to protect the availability of banknote cash.

A more logical argument for a digital pound is that cash – even if growing in use on a nominal level – is becoming a smaller component of overall money supply, since digital cash liabilities of the private sector are growing more quickly than central bank banknote liabilities. A diminishing component of cash in circulation should, however, still be enough to maintain a tether between the digital and cash worlds.

True Motivations

The more likely motivation for a digital pound is the growing public expense of printing and managing banknotes in the economy, especially in the context of the widely held view that physical cash remains the key gateway for criminal activity. The incentive to under supply the economy with banknotes due to these costs and risks is real and poses a legitimate financial stability risk. In the event of a financial crisis, the demand for paper banknotes could quickly outstrip the capacity of the Bank of England to supply them to commercial banks, creating the wrongful perception that the system as a whole was bankrupt.

If financial stability is the real motivation for a digital pound it should be explicitly stated as such in the consultation paper. While the concern is justified, there may be other ways to mitigate against such risks without resorting to the formal introduction of a digital pound – which brings with it financial stability risks of its own. A better mitigation might be to compel the Bank of England to set aside provisions for unexpected banknote demand by storing pre-printed but not-yet-circulated banknotes in reserve. Another option would be creating a digital national savings product – with varying maturity/expiry – that could be marketed to the public in the event of financial panics and other destabilising periods. The problem at the heart of the financial stability argument is a lack of risk-free savings options in the economy during a crisis, not a lack of means to conduct payments and transactions.

We used to have the Girobank for exactly this purpose. Millions of people had accounts. The government sold it off 20 years ago. Why not bring this back?

As to the second motivation: there is no evidence provided in the consultation paper to justify the assumption that a digital pound is needed to promote innovation, choice or efficiency. Given the risk that a CBDC crowds out private operators and challenges their access to cheap funding, it is just as likely that a digital pound will constrain and inhibit private sector innovation, choice and efficiency as encourage it. There is a significant risk too that the central bank will become overly dominant in the market for payments, and will stifle competition. This risk becomes all the more acute if the Bank were to become overly reliant on a digital pound for monetary policy purposes.

Monetary Policy

While the consultation paper does not envisage a digital pound being used for monetary policy, and states explicitly this is not a motivation for the project, this is not a reliable statement that the public can trust in. Central banks the world over have proven they are prepared to tear apart pre-existing rulebooks if circumstances justify it. It is impossible therefore to guarantee that in a national crisis the Bank would not be tempted to draw on the digital pound as a monetary policy mechanism or as a tool to achieve some other government objective.

Such action could conceivably involve applying negative or positive interest rates directly to retail accounts to influence inflation. It could also involve applying programmatic rules to limit or direct the circulation of money in the economy on a micro level or to regulate/inhibit demand to meet specific government objectives (for example by making it impossible for holders of digital pounds to spend their money at vendors deemed non-essential during an energy or health crisis, or to restrict carbon consumption).

Finally, it could involve raising or lowering caps on digital money responsively to financial conditions.

If the Bank ever saw fit to apply negative interest rates to a digital pound, this could potentially destroy trust in the Bank of England and the state, since it would effectively amount to a tax that has not been authorised by parliament.

Commercial Sensitivities, Data and Privacy Implications

The consultation foresees incorporating the principles of open banking into the design of a digital pound to stimulate innovation and efficiency. It specifically assumes that licensed institutions will be inclined to provide the customer-facing services (such as wallets) needed to support a digital pound economy.

It does not, however, explain why private sector providers would be incentivised to do this given all the usual pathways for them to monetise such services will be restricted under the proposed design. Banks make money either from the spread between the Bank rate and the rate they compensate depositors at, or by relending customer funds at a higher interest rate. The current design inhibits the capacity of banks to earn interest on deposits held at the central bank (since the digital pound is slated to be zero-yielding) or from lending activity, since digital pound deposits have to be fully-reserved. This means such funds will not form part of any bank balance sheet.

Other motivations for a digital pound are listed as enhancing financial inclusion, payments resilience and improving cross-border payments. But these assumptions lack evidence to support them. What’s more, it is unlikely that a limited proof of concept would ever be able to decisively corroborate or test such assumptions.

Given the inability of banks to make money from providing accounts (or wallets) in the usual way, it stands to reason that banks would have to find alternative ways to compensate for the cost of offering such services to customers.

It must be stressed that KYC/AML cost and risk is the primary reason why people are financially excluded in the UK. The same problems and costs apply to providing wallets for a digital pound wallet.

If we rule out a potential government compensation scheme to cover such costs, then the only cost-effective way for banks to recover their costs would be by charging fees. If citizens have to pay bank fees to access digital pounds, however, this will limit uptake and undermine the notion that the digital pound can help with financial inclusion – another alleged motivation for issuing it in the first place.

Given the above, the only viable way for banks to make money under a digital pound framework would be through the monetisation of citizens’ transactional data – notably by selling such data to third parties.

The transition to a data-funded economy would, however, turn centuries of established banking practice on its head and expose the system to many unknown negative externalities. The banking model has always relied on secrecy and discretion as an essential component of its offering to law-abiding citizens. It is that assumption that has through the ages cultivated trust in the banking system. If the public became fearful that banks were under commercial pressure to sell their data to third parties – potentially by socially engineering their inclination to opt into products that rely on access to their data – this could undermine trust in the entire banking system.

Rather than enhancing financial inclusion, such incentives would increasingly orientate the financial system towards a “if it’s free you’re the product” data economy.

This is a significant reconfiguration of the financial system, which in a democracy requires a clearcut public mandate, extensive parliamentary debate and even a potential referendum.

Data Serfdom Risks

The consultation paper foresees customers will be able to voluntarily opt into or out of the privacy levels that suit them. But, as we know from data practices in the existing tech economy, it is the poor and underprivileged who are always disproportionately forced to give up their privacy rights in such frameworks. It is they who cannot afford to pay the necessary privacy premiums. Rather than leading to a more inclusive world, the digital pound could, in such a scenario, tier society more heavily – if not split it decisively between the “have privacy and privacy have nots”.

The consultation paper seeks to reassure the public, many of whom are rightly fearful that a digital pound could be used repressively by the government or central bank to constrain political activists, dissidents, critics and journalists, by denying them access to economic goods and services.

It does so by arguing that the central bank (or government) will not have direct access to people’s data or be given any opportunity to influence how digital pounds may be individually programmed. This is not persuasive since the Central Bank and other government authorities and regulators have influence over the entities banks can and cannot serve by way of the anti money laundering (AML), combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) and know your customer (KYC) framework.

Programmability comes down to restricting what money can be spent on (in a broad sense including money in escrow arrangements dvp etc). This is useful for some large scale payments but has civil liberty implications for most retail payments. None of these programmability aspects by the way require a digital pound, and can be equally applied to the current framework.

There is little logic to the assertion that a digital pound will enhance payments resilience. On the contrary, giving the citizenry a risk-free asset to which they flee at the touch of a button, arguably adds fragility to the banking system not resilience.

Capital Control Risk

Last of all, there are insufficient grounds to assert that a digital pound has the capacity to enhance cross-border transactions. On the contrary, a digital pound introduces complex questions over who would be entitled to hold digital pound wallets and who would not relative to where they are in the world.

The consultation paper currently envisages universal access to the digital pound, with the ability of both UK residents and non-UK residents to use it in the UK or outside of UK jurisdictions. This fails to account for political risk associated with non-compliance with legacy exchange controls and/or other international laws that prohibit the use of non native currencies as a primary means of exchange in certain jurisdictions. There are also risks that countries hostile to the growing use of sterling transactions in their own jurisdictions could block access to digital pound wallets, thus increasing cross border frictions rather than alleviating them. A potential externality is the return of more heavily policed exchange controls and geofencing mechanisms throughout the world.

Narrow Banking

Creating a digital pound that prohibits private sector digital wallet providers from holding end users’ funds directly on their balance sheets reduces their capacity to cover the costs of providing such services from providing traditional banking services. This either creates a government liability, as banks will have to be compensated by the public purse to provide such services, or it will encourage them to monetise personal data instead.

Rather than enhancing the digital user experience, this dependency on a data-based business model risks introducing frictions, such as adverts and other distractions, to those who opt to have their data mined out of financial necessity. Those who opt out, on the other hand, are likely to experience higher transaction and service costs.

Making such funds inaccessible to bank balance sheets moves the UK closer towards a type of full-reserve or “narrow” banking system, which comes with its own economic implications.

A move to a narrow banking framework requires specific discussion in and of itself. Such a debate would have to draw on almost 90 years worth of academic research and inquiry into the pros and cons of a narrow banking system.

The issue of how the central bank itself will invest the funds it is allocated through the digital pound design requires further public, if not parliamentary oversight. If uptake is substantial, the central bank may be put under pressure to diversify its asset base beyond conventional government bonds. The risk in that case is that the model will encourage the central bank to compete in the conventional lending market on preferential terms, moving the financial system ever closer to a state-banking model. In this way the framework threatens the independence of the central bank.

Nobody can predict whether a digital pound will lead to a net increase in the Central Bank balance sheet or come at the cost of banknote demand. The risk remains the framework will open the door to more unfunded lending to the government.

The consultation document highlights that “the digital pound could make the Bank’s balance sheet larger and affect the level of central bank reserves, with potential implications for the volatility of short-term interest rates.” This is a substantial risk that cannot be under emphasised.

The consultation paper suggests balance sheet risk “can be managed by deploying the tools available to the Bank to ensure the demand for its liabilities is met.” And yet, at the same time, the paper glosses over any details. This seems a huge oversight given the capacity of such tools to meaningfully impact private sector asset prices. The only clue comes in a vague reference to “additional-backing assets”, envisaged as a balance-sheet offset to increasingly bloated digital pound liabilities.

Yes. But that does not necessarily guarantee citizens’ privacy will be respected or that back doors in the name of national securities won’t be introduced.

Privacy issues are not the only matter of concern. There is a risk that funds could at any moment be frozen or appropriated, based on anonymised but still meaningful data signals such as geolocation, frequency of transaction or other.

For as long as banks are subject to AML, KYC and CFT and licence-dependent they operate as de facto proxies of the state, meaning if they have access to personal data, government authorities in theory do as well. It is basically impossible, unless you have anonymous wallets based on a physical card or an anonymous mobile phone, which you can load, ironically, with banknotes via a physical agent to guarantee privacy either in a digital pound framework or the existing one.

Tiered access does not solve the compliance problem as criminals and money launderers will likely find ways to bypass quantitative limits by using third parties, fake personas or high frequency bots. To manage risks wallet providers may end up discriminating against customers in other ways.

There may also be implications for how citizens raise money for political or activist causes using digital pounds.

Giving users the ability to opt into how much privacy they give up or do not give up, does not prevent social norms from arising that could make it impossible to access goods and services unless certain rights are given up. This is already self-evident in the digital economy where powerful incumbents and monopolies can dictate terms and conditions to users, leaving them without any other option but to give up their rights if they are to access key services critical for modern life.

The greatest organic demand for a digital pound is likely to come about during a financial crisis or during a period of negative interest rates. This would suggest the highest priority payments should be between private sector accounts and digital pound accounts, a.k.a the ability to on and off ramp into the digital-pound ecosystem. It is not clear that there is a public interest in making these sorts of transactions frictionless and immediate given the financial stability and monetary policy risks.

Limits of £10-£20k would do little to reduce financial stability risk since the vast majority of the population does not have access even to such low sums. The sums are also too high to prevent innovative criminals and money launderers from abusing or utilising transfer mules to get around them.

If corporates cannot hold digital pounds this defies the point of a digital pound, since what good is a digital pound if it cannot be redeemed for goods and services, which are disproportionately provided by corporates? Limits on corporate use would be untenable since business is open-ended, and even if a rule was made that forced corporates to convert digital pounds into private sector money beyond a certain threshold, this would introduce complexity and cost into the business sector (especially for SMEs) rather than any efficiency or productivity gain. If corporations were to be given higher allowances, this would defy the logic of having limits at all, since criminals and money launderers would be encouraged to open digital corporations engaged in digital-only business to get around restrictions.

If restrictions were made on the type of corporations that can accept digital euros, with a preference for those engaged in bricks and mortar activities, this would undermine the assertion that a digital pound would be good for digital innovation and or the digital transformation of the country.

Any corporate holding significant holdings of digital pounds would essentially have a quasi-central bank reserve account. This is an important point that needs to be discussed in isolation.

Broad financial inclusion is inhibited in the digital realm by the fundamental clash between the need to comply with anti money laundering and know-your-customer regulations and to provide access to all citizens. The assumption that tiered access will somehow reduce financial crime while continuing to allow universal access to public monetary goods is naive. Algorithmically programmed velocity would likely compensate for quantitative restrictions. Measures to curb transaction frequency, as well distribution (how many wallets can be created per communications device) would also have to be brought in to curb financial crime. the latter would be impossible to police without undermining the supposed point and purpose of central bank digital currencies, notable efficiency and financial inclusion. It is a paradox.

According to the Equality Act 2010 it is against the law to discriminate against someone because of their age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex or sexual orientation.

The introduction of a digital pound potentially discriminates against Christians who might consider it a manifestation of biblical prophecy and thus be reluctant to use it. If they are forced to do so against their wishes out of necessity (for access to essential goods and services) this would be discriminatory and coercive. The digital pound also discriminates against the elderly and those who are not au fait with technology.

source : https://the-blindspot.com/a-comprehensive-critique-of-britcoin-youre-welcome/