Martin C W Walker

In October 2020, the Bahamas launched its central bank digital currency (CBDC), called the “sand dollar”. The sand dollar project has been greatly praised, described by PwC as the “world’s most mature CBDC”. An article published by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum described it as a “groundbreaking innovation” and according to the Central Bank itself, “The Bahamas is considered a global leader in CBDC development”.

While many pundits point to developments in China as an example of technological advances in fintech, the example of the sand dollar may be more relevant to much of the rest of the world. The Bahamas is a democratic, developed, free-market economy. Like in most developed nations, the central bank publishes regular and accurate data about its balance sheet. Data that provide a genuinely objective and hype-free view of the success of the sand dollar.

To consider the currency’s success, it is worth stating the basic questions that are so often forgotten by those who write about fintech:

- Is there a clearly defined problem to be solved or opportunity to be exploited?

- Is the problem worth solving?

- Is there a clearly defined solution for the problem?

- Is there evidence the solution was an improvement on the status quo?

- Are there alternative solutions that may be a better fit?

The fundamental problem addressed was financial exclusion, particularly in the more remote parts of the archipelago that makes up the Bahamas. A Central Bank of the Bahamas report in 2019 stated: “Although average measures of financial development and access in the Bahamas are high by international standards, pockets of the population are excluded because of the remoteness of some communities outside of the cost-effective reach of physical banking services”. The main proposed benefit was “financial inclusion – improved access to digital payments for the unbanked and underbanked.” The general theme that there were pockets of financial exclusion in more remote areas of the Bahamas has continued throughout communication about and analysis of the sand dollar. Initial analysis also claimed potential benefits in a wide range of areas including reduced transaction costs, faster transactions, reduced tax evasion, and more effective information gathering by the government.

Reviewing the data gathered before the initial pilot and subsequent research does not strongly support financial inclusion as a reason for introducing a Bahamian CBDC. The initial pilot for the sand dollar was on a group of islands called Exuma (part of the Family Islands). The research did not show that exclusion from the financial system was particularly problematic by global levels. Ninety-three per cent of Exumans had some form of deposit account and 90% had a debit card. In South Korea (which has a similar level of GDP per head) 94.85% of people aged 15 or over had a bank account or an account at a mobile money provider. In the US and UK, 95% and 97% of adults respectively have bank accounts. The percentage of Exumans holding accounts was shown to be lower that the Bahamian average by subsequent research, which estimated 94.3% of Bahamian adults had some kind of account. The group with the lowest rate of account ownership were those aged 55 and above. Those most typically resistant to using digital payments.

The sand dollar was a clearly defined solution to the problem of lack of access to digital payments. The majority of the population were made aware of it and starting a digital wallet was a straightforward process. However, the real problem arose when measuring the impact of the Bahamas CBDC. A paper published this year by the central bank claimed to have “determined that there is a positive correlation between CBDC and financial inclusion.” It also described an “adoption rate” or “roughly 7.9%”, with 32,736 wallets having been created. The picture is not quite so positive in an IMF (International Monetary Fund (IMF) report published in May this year, which claimed that “the CDBC currently makes up less than 0.1 per cent of currency in circulation and there are limited avenues to use the sand dollar”. However, it was still generally positive about the sand dollar and its “potential to help foster financial inclusion and payment system resilience.” Going on to recommend that the central bank, “accelerate its education campaigns and continue strengthening internal capacity—including on cybersecurity—and oversight of the CBDC project to safeguard financial integrity.”

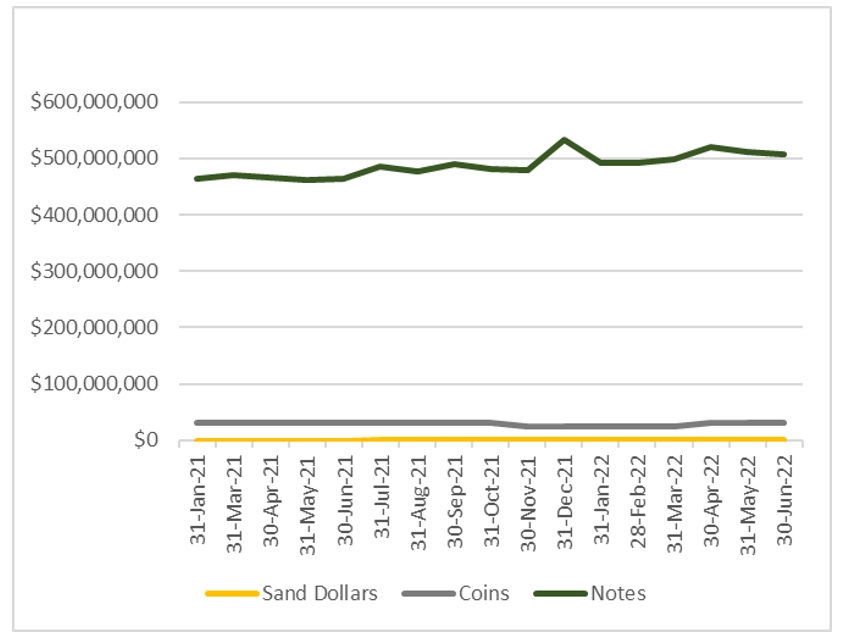

Reviewing the monthly data from the Central Bank of the Bahamas on their assets and liabilities shows a painfully slow rate of adoption and much lower proportion of currency in circulation than even the IMF indicated (Based on the June 2022 data, a more accurate value would be 0.0631% of currency in circulation). There was a brief period of fast growth in mid-2021 (as shown below) but it was from an extremely low base and seems to have levelled off.

Even those numbers do not give the true picture unless put in the context of the overall amount of currency in circulation and the growth in other forms of central bank-issued currency, such as coins and notes. By June this year, almost two years since the launch, there were still only $338,908 in circulation. To put that into context, there are over $30m in coins in circulation, plus almost $506m Bahamian issued bank notes (plus at least as many US dollars). With a population of around 393,000 people, that means the per capita circulation of sand dollars is around 86 cents, compared to a per capita circulation of $78 in coins and $1,287 in Bahamian notes (see table below).

Between January 2021 and June 2022, sand dollar balances grew by less than $300,00 compared to a $42 million dollar increase in the value of notes, meaning the sand dollar barely registers as a form of currency. Even the value of coins in circulation has increased more in dollar terms. With such a tiny circulation, it is safe to say using metrics such as the number of wallets created as a measure of adoption (7.9%) is close to meaningless.

Finally, in terms of alternatives, debit cards and pre-paid credit cards, which can be used with existing payment systems, are accepted by a far greater number of merchants, and continue to overshadow any progress made by the sand dollar.

The lessons of the sand dollar (to-date) apply to all CBDC projects, if not fintech innovations in general. Firstly, they need to be aimed at real problems. Financial exclusion in the Bahamas does not seem to be a major problem by international standards. Secondly, the proposed solution needs to genuinely solve the problem (even if relatively small). The minimal impact of the sand dollar to date suggests it does not. Finally, “pilots” of the type so frequently carried out in fintech, particularly by central banks, need to be re-considered as a form of proof. Simply implementing something, judging whether it “works” is not a good guide for either policy making or commercial investments, unless there is an objective evaluation of alternatives. In the case of the sand dollar, the obvious alternative to creating a new payments and banking infrastructure would have been to encourage greater use of bank issued debit cards and more efforts to educate the older generation in the use of electronic payments.

source : https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2022/11/22/how-is-the-worlds-most-advanced-central-bank-digital-currency-progressing/